RCA Certificates Railbelt Reliability Council as Alaska’s First Electric Reliability Organization

Although it is editorially independent, the Alaska Energy Transparency Project receives funding from AKPIRG, which currently holds a seat representing consumer interests on the RRC Board.

A glossary of technical terms can be found at the end of the article.

By Brian Kassof

On September 23 the Regulatory Commission of Alaska (RCA) certificated the Railbelt Reliability Council (RRC) as the Electric Reliability Organization (ERO) for the Railbelt power grid that serves users between Fairbanks and the Kenai Peninsula. The RRC has the potential to reduce future electricity prices, diversify sources of power generation, and bring more reliable service to Railbelt consumers. This is a significant step in a process that began in 2015. The RRC will be responsible for planning future power generation and establishing and enforcing transmission and reliability standards for Railbelt electric utilities.

The RRC has submitted a proposed budget, its tariff (a listing of services provided and dues to be paid by utilities), and proposed rules for its operation to the RCA for approval. Members of the public can access these documents and submit comments on the tariff to the RCA (see the Next Steps section below for more details on how). If the budget and tariff are approved, the RRC will begin hiring staff and developing regulations in fall 2023.

Regulators, state officials, and consumers have long believed that the lack of coordination and cooperation among Railbelt utilities has led to inefficiencies and missed opportunities for collaboration, creating higher prices and less reliable service. An RCA memo to the Legislature in 2015 laid out the challenges and made recommendations for greater integration and cooperation. This led, after a number of failed, utility-led attempts at greater integration, to the 2020 passage of Senate Bill 123 (SB 123), requiring the creation of a Railbelt ERO.

The RRC will oversee aspects of the work of the six Railbelt utilities that together provide power to 75 percent of Alaska’s population. These are four electric cooperatives–Homer Electric Association (HEA), Chugach Electric Association (CEA), Matanuska Electric Association (MEA), and Golden Valley Electric Association (GVEA)–as well as Seward’s municipal Electric Department and Doyon Utilities (which serves several military installations).

The RRC will have three primary functions. It will oversee the development of an Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) that will look at the collective generation needs of the Railbelt over the next twenty years and designate a combination of projects to best meet them. It will develop interconnection and transmission standards, ensuring that power producers have equal access to the transmission system. Lastly, it will develop uniform reliability standards for electric transmission (including cybersecurity) for the entire Railbelt. Standards development should begin in 2024. Completing the IRP will likely take three to four years.

These three functions are closely interrelated. A more robust and reliable Railbelt transmission network will allow more power to move through the system, making it possible for the IRP to coordinate the development of new generation facilities to serve the entire Railbelt. This will bring an end to the current practice of each utility focusing on meeting its own generation needs, which has led to an overbuilding of generation capacity in the Railbelt in the past fifteen years at great cost to consumers. It will also make it easier for independent power producers to sell to utilities beyond their immediate area, increasing competition and facilitating the integration of renewable energy.

The remainder of this article takes a deeper dive into aspects of the RRC, and is divided into the following sections:

--What is an ERO?

--What Will the RRC Do and Why It Matters to Railbelt Consumers

--The RRC’s Organization and Structure

--Next Steps

--Why is the RRC Necessary?

--How the RRC Was Created

What Is an ERO?

Over the past thirty years EROs have become increasingly important for regulating transmission and enforcing reliability standards across the Lower 48. There are several different types of EROs, each with its own range of responsibilities, from establishing and enforcing standards to operating transmission systems and power markets. The RRC’s primary tasks will be regulation, coordination, and planning—it will establish and enforce standards and develop a generation plan, but not operate systems or oversee an energy market.

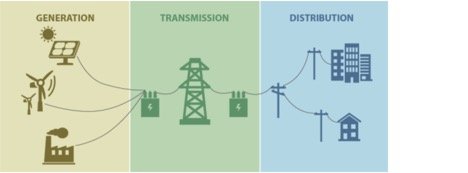

To understand the RRC’s mission it is useful to define the three main components of an electric power system: Generation, transmission, and distribution. Generation is the production of power from fossil fuels, solar and wind farms, hydroelectric plants, and other facilities. The transmission system is the high-voltage lines that transmit large amounts of energy from the generators to the distribution systems. Distribution systems are local networks of substations and power lines that take transmitted energy, step down its voltage, and deliver it to consumers. The RRC will focus on the transmission system, along with planning for new generation facilities. It will not be involved with the local distribution systems operated by utilities.

3 main components of an electric power system

(Image source:Congressional Research Service)

What Will the RRC Do and Why Does It Matter to Railbelt Consumers?

Transmission and Interconnection Rules:

The RRC will have multiple responsibilities relating to the transmission system. One will be to ensure that all power producers have equal access to it. Another will be to create guidelines to equitably distribute the cost of its future expansion. Having an outside body oversee these aspects of the transmission system is necessary because the actual transmission lines are owned by a variety of entities—the four electric cooperatives own most, but the Alaska Energy Authority (AEA, a state-owned corporation) owns the Intertie section connecting Interior Alaska to the rest of the Railbelt and some of the transmission lines from the Bradley Lake Hydroelectric project, and Seward Electric owns the transmission lines connecting it to CEA’s system.

The RRC will establish “open and non-discriminatory” interconnection and transmission standards (enforceable technical rules) that govern how power generators connect to the transmission system and how the power they generate is treated as it moves through it. Currently each Railbelt cooperative has its own rules for interconnection and transmission—the RRC will create common standards that cover all of them.

Interconnection and transmission standards will make it easier for independent power producers to understand the requirements for connecting to the transmission system. (Independent power producers are privately-owned and operated generation facilities that sell wholesale power to utilities). The RRC will also standardize the rules governing the use of the transmission system. Lastly, it will guarantee the ability of any power producer willing to meet the technical requirements and to pay associated infrastructure costs to connect to the transmission system. Open access is allowed under existing utility tariffs, but each utility has specific rules and tariffs subject to periodic renewal, which can change with RCA approval.

The RRC will develop a Transmission Recovery Cost Standard that creates a framework for equitably distributing the costs of updating the transmission system to meet new reliability standards. The Transmission Recovery Cost Standard should also facilitate needed expansions of the transmission system. Currently there are only single, 75-megawatt capacity transmission lines connecting the Interior and the Kenai Peninsula to the rest of the Railbelt. This limits the amount of power that can be transferred between regions, constraining the greater integration of the Railbelt system. The existing interregional transmission lines were financed primarily by the state in the 1980s and 1990s using oil revenues.

Funding for the expansion of the transmission system will likely have to come from the utilities or from federal grants that require utility cooperation. Utilities will invest only if they expect proportional benefits. The RRC’s Transmission Cost Recovery Standard will make infrastructure expansion easier, providing a formula to divide the costs of projects that benefit more than one utility. This is critical for greater system integration, which, in turn, will allow for more renewable generation such as wind farms in the Interior and hydroelectric generation on the Kenai Peninsula. Larger power systems can more easily integrate large amounts of variable renewable power from sources such as wind and solar--the larger the system, the less impact local variations in wind or sun will have. A larger system also draws power from more diverse sources, making it easier to balance production with demand.

There are several critical aspects of the present transmission system whose fate under the RRC remain unclear. The most important are “wheeling fees,” charges leveled by utilities when a power generator wants to transfer power across the utility’s transmission system to another buyer. Currently each utility is allowed to charge its own wheeling fees for power transmitted across its system—as a result, a producer transmitting power across the lines controlled by multiple utilities can be charged a separate fee by each, paying what are known as “pancake rates” (since they are stacked atop one another).

Pancake rates make it very difficult for power generators to sell power to utilities in other regions. In the mid-2010s the Fire Island Wind Farm near Anchorage tried to strike a deal to sell power to GVEA in Fairbanks. Fire Island already sold some of its power to CEA, but the utility was uninterested in purchasing more. GVEA wanted to buy electricity from Fire Island, but the power would have to be transmitted through CEA and MEA’s systems to reach the Interior. Each utility wanted to charge a separate wheeling fee—these pancaked rates made Fire Island power uneconomic for GVEA, scuttling the deal.

Pancaked rates make it difficult for independent power producers to sell power to anyone except their local utility. By allowing independent producers to reach more potential customers, their elimination could create a more competitive power market. The RRC could one day introduce a universal transmission rate (also known as a “postage-stamp rate”)—a single transmission fee (measured by the amount of power transmitted) regardless of how many transmission territories the power passes through.

The RRC also could remove other obstacles for independent power producers by capping and standardizing ancillary fees charged by utilities for transmission services. These fees include charges for “reactive power” (essentially the energy needed to regulate voltage and push power up and down transmission lines), “spinning reserves'' (back-up power that can be used to replace the power a generator is putting into a system if they should suddenly go off-line), and similar services. Like wheeling fees, each utility sets its own rate for these services.

Neither SB 123 (the 2020 Alaska law authorizing the creation of a Railbelt ERO) nor the RCA’s interpretation of the law make it clear if the RRC has the responsibility and/or authority to address questions such as pancake rates or ancillary fees. It will be up to the RRC’s Board to decide whether these issues fall within their authority and if they wish to tackle them.

Reliability Standards:

The RRC’s second area of responsibility for the transmission system is the creation and enforcement of reliability standards. Reliability, in this context, means making sure that the lights do not go out, and, if they do, that power can be restored quickly and safely. This means setting basic minimum capacity and performance standards for equipment and ensuring emergency plans are in place if parts of the system fail. As the Railbelt becomes more interconnected, the importance of such plans grows, as was demonstrated in July 2022, when a downed transmission line in Fairbanks caused brief outages throughout the Railbelt.

Reliability standards will also require decisions about how to balance efficiency with built-in redundancy. A robust, interconnected power system requires redundant capacity that can be used to reroute power when part of the system is knocked off-line. But this extra capacity costs money, so calculations must be made about how to balance risk and cost throughout the system. This is a particular challenge in the Railbelt with its largely linear transmission system.

Reliability also includes protecting transmission systems from both physical and cyber threats to their operational integrity. Most Railbelt utilities already follow a common set of reliability standards (HEA being the exception). The RRC is expected to review these existing standards, update them where appropriate, and ensure they are followed throughout the Railbelt. Unified standards will be particularly important if the expected upgrades are made to the system over the next two decades.

Integrated Resource Planning (IRP):

The final aspect of the RRC’s mission is the creation of an IRP. This plan will forecast anticipated power demand in the Railbelt over the next twenty years and identify what generation sources (existing and future) will best meet those needs. By looking at the collective needs of the Railbelt utilities and other grid users, instead of having each utility focusing on its own generation needs, the IRP is intended to use joint planning to minimize costs and maximize the benefits of any new generation projects.

The process for developing the IRP is intended to balance a number of criteria. Foremost among these are cost, reliability, and adherence to local and national rules. The IRP will also weigh other factors, such as environmental impact. Another criterion will be system resiliency–how well a proposed generation project will stand up to Alaska’s challenging environment, the possible impact of climate change, and the projected availability of different types of fuel.

One important function of the IRP will be to lower the barriers facing independent power producers. Alaskan utilities have tended to favor the development of their own generation facilities over the purchase of power from independent producers. Since it will be focused on collective needs, the IRP will select whichever projects will most benefit Railbelt consumers without consideration of ownership. Ensuring that the most economical and beneficial projects are built should open up more opportunities for independent power producers, increasing competition and bringing down the future cost of power for ratepayers. Since independent power producers are largely focused on projects fueled by renewables (such as wind and solar), this should also help the Railbelt utilities achieve their carbon reduction goals.

In the past Railbelt utilities were able to build generation projects without RCA permission (they had to get RCA approval to bring them on-line, but not for construction, and it was unlikely the RCA would refuse to allow a project to go on-line once it was built). Under the RRC utilities will still be able to build their own new generation facilities, but any new utility-owned project (or major upgrade of an existing facility) will either have to be part of the IRP or receive pre-approval from the RCA. Although proposed generation projects from utilities will be considered as part of the IRP, the RRC cannot compel a utility to build any new generation facilities.

It is worth noting that, while the RRC does achieve some key reforms, it does not meet all of the goals set by the RCA in its 2015 memo. It does not create an independent body to operate the transmission system (often known as a Transco or a Unified System Operator). Nor does it have the authority to ensure that power demand throughout the Railbelt is met by using the least expensive available source of power generation, regardless of ownership (an approach known as “economic dispatch”).

The RRC’s Organization and Structure

The RRC is led by a governing board consisting of thirteen voting directors and two ex-officio members. The voting members of the Board represent six Railbelt utilities (CEA, MEA, GVEA, HEA, Seward Electric, and Doyon Utilities), AEA, independent power producers (two seats), and consumer advocates (three seats), along with one independent director. Each board member also has an alternate who can act in their place if the director is unavailable. The ex-officio (non-voting) members represent Alaska state agencies: the Regulatory Affairs and Public Advocacy Office of the Department of Law and the RCA. (Here is a list of RRC board members)

The RRC’s board composition was the product of long debate. While some EROs are governed by independent boards (whose members have no current affiliation to the utilities or power producers regulated by the ERO), the RRC has a board consisting primarily of stakeholders, along with one independent seat (this is known as a “hybrid board”). The seats on the Board are meant to balance evenly between those representing power providers and power consumers. It should be noted that many of the seats on the Board are considered to represent both providers and consumers—this is true of the four electric cooperatives, the Seward Electric Department, and AEA.

One important aspect of the RRC’s board composition is the role played by the Railbelt utilities, who hold six of thirteen voting seats on the Board (it is not clear what will happen to the city of Seward’s seat if it goes ahead with a proposed sale of its electric utility to HEA). It is not uncommon for stakeholders to have seats on ERO boards. Representatives of the utilities have consistently argued that their participation on the Board is critical to its success, since they have the best understanding of the electric system, the needs of Railbelt customers, and the unique challenges of operating an electric grid in Alaska.

However, there are certain tensions inherent in the utilities’ critical role in a body created to compel their cooperation and regulate aspects of their business. As a result, there have been complex negotiations about how to deal with potential conflicts of interest. One solution has been to divide the Board into eight stakeholder classes, with certain actions requiring the approval of not only a majority of board members, but also the majority of stakeholder classes.

Despite these steps, some observers are still worried about the utilities’ role on the RRC Board. In the summer of 2022 one Board member and one alternate resigned their seats, both expressing concerns about the utilities’ dedication to having the RRC operate as an authoritative and independent body. In his resignation letter, Hank Koegel, who had held the independent seat on the Board, expressed a fear that the utilities might be using the RRC to advance their own agenda without real input from other stakeholders. Mike Craft, who was the alternate for one of the independent power producer seats, was blunter in a statement he made announcing his resignation, stating that the utilities were moving the ERO away from the intentions of SB 123 and had “completely shanghaied the whole process.” (Craft, who operates a wind farm in Delta Junction, has frequently clashed with GVEA over potential generation projects.)

One area of concern has been a failure of some utilities and AEA to notify the RRC Board of significant projects or initiatives that could have a major impact on the Railbelt grid. A comment submitted to the RCA by the Alaska Independent Power Producers’ Association (AIPPA) in August listed nine major projects backed by the utilities or AEA since the start of 2022 that AIPPA believed had not been disclosed to the RRC Board in a timely manner. In the opinion of AIPPA, this demonstrated a lack of commitment to the IRP process. AIPPA currently nominates candidates and alternates for the two independent power producer seats on the RRC Board.

Another area of concern is the utilities’ challenges to policies already approved by the RRC Board. All four cooperatives and the City of Seward applied for and were granted status as “intervenors” for the RCA’s hearings on certificating the RRC. While all expressed support for the RRC’s certification, they used their intervenor status to challenge parts of the application that had already been approved by the RRC Board. The utilities argued that their interventions largely were driven by concerns about costs, and that they were compelled to defend their ratepayers’ interests.

Several other organizations represented on the RRC Board, such as AIPPA, the Renewable Energy Alaska Project (REAP), and the Alaska Public Interest Research Group (AKPIRG) also submitted additional comments to the RCA during the certification process. These comments were generally positive, and these organizations did not seek intervenor status.

This practice of utilities asking the RCA to change RRC policies after they have been approved by its Board has continued after certification. In mid-November MEA sent a comment to the RCA challenging the confidentiality rule already approved by the RRC Board. (MEA has since stated that it wants to retract the comment, which it says should have gone directly to the RRC Board.) In the same letter, MEA indicated that it planned to use the RCA’s review of the RRC’s proposed tariff as an opportunity to argue for policies that the RRC Board has chosen not to adopt.

For their part, the utilities have repeatedly stated that they are supportive of the RRC and its mission, even if they have concerns about specific policies. They also argue that their actions are intended to watch out for the interests of their ratepayers, who will be paying for the RRC–MEA reiterated this argument in their most recent comment to the RCA.

The Board will set policy and oversee the work of the RRC’s CEO. The Board will also approve any transmission standards and the IRP before they are submitted to the RCA. It will be able to hire subject-matter experts to help it understand the policies developed by RRC staff. The availability of such experts to assist the Board is important, since some board members, such as those representing the utilities, have industry knowledge and technical expertise (or access to these resources) that other members do not. The availability of subject experts to the entire Board is intended to prevent those members with greater technical resources from exercising undue influence on board decisions.

The CEO will hire and oversee the RRC’s technical and administrative staff. There will be a Technical Advisory Council, consisting of senior engineers and the CEO, which will support and coordinate the activities of the different technical sections. The individual sections will be responsible for overseeing specific parts of the RRC’s mission (Standards, Planning, Research Studies, Compliance and Enforcement).

The development of specific standards and the IRP will be carried out by dedicated Working Groups. These groups will be led by RRC engineering staff, and will include subject-matter experts, representatives from different stakeholders, and interested members of the public. Any member of the public over the age of nineteen can apply to participate in an RRC Working Group; technical expertise is not required, although applicants should be able to explain their interest and why their perspective would be valuable to the Working Group. The Working Groups’ recommendations will be submitted to the Technical Advisory Council for review, and then to the Board of Directors for approval. Transmission standards, reliability rules, and the IRP will then be submitted to the RCA for final approval; only then will they go into effect.

Next Steps

Now that the RRC has been certificated as the Railbelt’s ERO, it must submit a number of documents to the RCA for approval. These include the rules that will govern its operation, its 2023 budget, and its tariff (a listing of services provided and dues to be paid by utilities). The RRC’s most recent budget proposal was submitted together with its proposed tariff on November 23 (this superseded an earlier budget submitted in October). The budget is considerably different from the one submitted with the RRC application in April 2022--($1.5 million as opposed to the initial estimate of about $4.5 million for 2023). The reduction is due largely to the fact that the original proposal foresaw the RRC entering into full-scale operation in 2023; the new budget only includes salaries for the CEO and their support team for the last three months of 2023. Because the RCA reduced the number of technical specialists it will hire, future budgets will be lower than were initially anticipated. It is expected that the RRC’s annual budget will go up and down in future years—it will be highest in the first full years of operation, as transmission and reliability standards are adopted and the IRP developed, then go down once these tasks are completed and work shifts to compliance monitoring, and updating standards and the IRP.

On November 16 the RCA announced it was opening an investigation into the budget the RRC submitted in October. The RCA uses investigations to examine instances when a filing may not correspond to state statute or RCA rules–it is not an indication of any wrongdoing. The decision came after the state Attorney General’s office raised several questions about the budget. An initial hearing is scheduled for mid-December–it is not clear what impact the submission of the updated budget in November will have on this process.

The RRC submitted its proposed Rules for operation to the RCA on October 10. On November 14 the state Attorney General’s office raised a number of technical problems with the Rules, such as inconsistent uses of terminology and instances where they might not match state statute. Because of the large number of issues raised by the Attorney General’s office, the RRC’s Board decided on November 18 to withdraw the Rules, redraft them to address these problems, and resubmit them by December 12. Because the Rules are being withdrawn and resubmitted, there will be a new 30-day public comment period after they are received by the RCA, starting on the day they are posted. (The RRC’s revised rules can be found here—updated 12/13/22).

The RRC’s tariff was submitted to the RCA on November 23. The tariff requires RCA approval before it goes into effect, and the RCA will be accepting public comments on the tariff until December 20. The approval process will take a number of months, and the final decision may not come until May 2023. If the tariff is approved, the RRC will then be able to start charging a fee to the Railbelt utilities, which will be apportioned based on the amount of power each utility sells. (The Railbelt utilities have agreed to pay the RRC’s current, limited costs until the tariff is approved.)

For those interested in commenting on any of the RRC documents currently before the RCA: The RCA’s investigation into the RRC’s October budget is RCA Matter E-22-002. The Rules are RCA Docket ER-1 9001. The tariff is RCA Docket TE1-9001.

The Railbelt cooperatives are still deciding the specifics of how the cost of the RRC will be passed on to members. Spokespeople from several cooperatives have indicated that the Railbelt utilities are working to develop a uniform approach to this issue. The utilities could fold the RRC costs into their existing rates. However, spokespeople from MEA, GVEA, and HEA have said that, in the interest of transparency, they expect the utilities will include the RRC fee as a surcharge that will appear as a separate line on customers’ monthly bills. GVEA and HEA have indicated that the surcharge will likely be based on each customers’ monthly power usage, although this has not been finalized. For most residential customers the surcharge in 2023 is likely to be under $1 a month, although it will increase in subsequent years, as the RRC reaches full functionality. The surcharge will not appear until after the RRC’s tariff is approved.

After the RCA approves the RRC’s tariff, the Board plans to hire a CEO by the fall of 2023. The CEO will oversee the hiring of the rest of the staff, a process that is expected to stretch into the spring of 2024. Once the staff is in place, the RRC will become fully operational, and it will begin its work developing transmission and reliability standards, and start the process of drafting the IRP.

Why is the RRC Necessary?

Because of Alaska’s history and geography, its electric utilities were founded in isolation from one another. Their small markets made them unattractive to commercial utilities, so they were set up as rural cooperatives or municipally-owned systems. Over the years the Railbelt utilities became more connected, a process completed by the opening of the Intertie Transmission Line connecting Fairbanks to the rest of the Railbelt in the 1980s. The 1991 opening of the Bradley Lake Hydroelectric project, which provides power to all the major Railbelt electric utilities, further connected them. Most of the utilities in Southcentral were also linked by power sales agreements with CEA, which provided power to other utilities for decades.

But, as then-RCA Chair Robert Pickett noted in a 2008 report, coordination and cooperation among the Railbelt utilities continued to be intermittent and irregular, and frequent disputes between them led to costly litigation. Between 1998 and 2011 there were multiple studies and reports that considered the advantages of greater integration among the Railbelt utilities and suggested possible structures for achieving this. But none were ultimately implemented, in part due to resistance by the utilities. (Here is an excellent summary of these efforts compiled by REAP)

Around 2010 MEA and HEA, which had previously purchased the bulk of their power from CEA, decided to construct their own generation plants. This was part of an unprecedented building spree by all four Railbelt cooperatives and Anchorage’s Municipal Light and Power (ML&P, which was purchased by CEA in 2019). According to an RCA presentation to the Legislature, between 2010 and 2017 each of these utilities either built or purchased significant new generation plants at a combined cost of $1.5 billion. Critics pointed out that this approach, which focused primarily on meeting local needs, risked wasting resources and creating higher energy prices.

These concerns seemed to have been justified. According to figures from the Alaska Center for Energy and Power (ACEP), Railbelt electric generation capacity, which was just above demand in 2010, increased from 1400 megawatts to 2000 megawatts (about forty percent) over the next eight years. Demand over the same period, meanwhile, actually declined by about one percent a year.

How the RRC Was Created

This large, and largely uncoordinated, spending spree caught the attention of members of the state legislature, who commissioned the RCA to draft a report on the current state of the Railbelt utilities and recommend reforms. The RCA partnered with ACEP to carry out the project, and their findings were submitted to the Legislature in June 2015.

The report confirmed that the Railbelt utilities’ lack of integration and coordination was leading to higher electric rates for customers. It also highlighted the need for major upgrades in the Railbelt transmission system if the utilities were going to become more integrated. The report stated bluntly that major institutional reform was necessary to create a more “effective and efficient” system, and made five recommendations to achieve this end.

The next years saw halting steps toward addressing the RCA’s recommendations, including an attempt to create a “Transco” (an independent company to operate the transmission system). The Transco was abandoned in June 2019 due to the withdrawal of CEA and MEA, and in light of concerns voiced by the RCA. There was also an attempt to integrate the generation capacity of some of the Southcentral utilities (the creation of a so-called “tight pool”), but this was suspended during CEA’s purchase of ML&P in 2019. (The RCA ordered the reinstatement of this tight pool after the sale was completed, but it only functioned for part of 2021, before breaking down due to a still-unresolved disagreement over accounting methods between CEA and MEA). Meanwhile, all the Railbelt utilities agreed publicly that the creation of an ERO was a good idea, but they continued to disagree about the specifics.

The first proposal for an ERO using the name RRC appeared in 2018 in a plan put forward by six Railbelt utilities (CEA, MEA, HEA, GVEA, ML&P, and Seward Electric). This initial iteration was viewed as a complement to the Transco that was being contemplated at the time. This agreement became moot when the creation of the Transco was abandoned in 2019.

In 2019 legislation on the creation of an ERO was introduced into both houses of the Alaska Legislature. The bills were introduced at the behest of the RCA, which had two concerns. The first was that voluntary attempts by the utilities since 2015 had not led to any tangible results. The second was that some believed the RCA lacked the statutory authority to regulate an ERO if one were created. The legislation was seen as a solution to both problems—it would either spur the utilities to come to an agreement or force one upon them, and it would grant clear regulatory authority to the RCA.

After requesting, unsuccessfully, that the legislation be delayed while they continued to negotiate the creation of an ERO, in December 2019 the utilities signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that provided a basic framework for an ERO using the name RRC. Critics of the utilities’ role on the RRC Board, such as Mike Craft, have argued that the utilities signed the MOU in an attempt to gain control over the future ERO. The utilities and the RCA maintain that the utilities’ support and involvement at this stage were critical to the successful creation of an ERO.

The signing of the MOU cleared the way for the passage of SB 123 in March 2020, which provided statutory authority for the RCA to oversee the creation of an ERO for the Railbelt and delineated its structure and functions. In the end, the ERO was a compromise between the different utilities and other interested parties, such as independent power producers and consumer advocates. SB 123 addressed some of the recommendations from the 2015 RCA memo, but did not include the creation of a Transco or the implementation of “economic dispatch.”

After the passage of SB 123 the RCA was tasked with adopting the Legislature’s instructions into a set of regulations (part of the Alaska Administrative Code) defining the rules governing the ERO’s operations. In July 2020, representatives of the utilities, together with other stakeholders, formed an Implementation Committee to draw up the organizational rules for the RRC. This Implementation Committee would eventually become the RRC’s Board of Directors. The RCA submitted its regulations in June 2021 (see this AETP article for more details). Review of the proposed regulations by the Department of Law, including several discussions about whether or not they corresponded to the text of SB 123, lasted until December 2021, with the final approval of the regulations coming in January 2022. This allowed the RCA to open a window for applicants to become the ERO. The RRC, which submitted an application in late March 2022, was, as expected, the only applicant.

Technical terms used in this article:

Transco—Independent transmission company operating a bulk-electric delivery system serving multiple utilities.

Wheeling Fees– charges leveled by utilities to allow a power generator to transfer power across their transmission lines to another buyer

Pancake Rates—when a power generator is charged wheeling fees by multiple transmission operators to move power from one place to another

Tight Pool–an agreement where multiple utilities agree to draw upon their collective generation assets, using the least expensive source of generation available to meet demand

Economic Dispatch–similar to a Tight Pool; a system where an independent operator directs power from the least expensive generation source available, independent or utility-owned, to meet need across a region.

Tariff—a listing of services provided and fees charged by a public utility. All Alaskan utilities (including the RRC) must file a tariff with the RCA.

Acronyms used in this article:

ACEP—Alaska Center for Energy and Power—research institute at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks

AEA—Alaska Energy Authority, a state-owned corporation charged with reducing energy costs in Alaska

AIPPA—Alaska Independent Power Producers’ Association

AKPIRG—Alaska Public Interest Research Group—consumer interest group

CEA—Chugach Electric Association—electric utility serving greater Anchorage area

ERO—Electric Reliability Organization

GVEA—Golden Valley Electric Association—electric utility serving greater Fairbanks area

HEA—Homer Electric Association—electric utility serving western part of Kenai Peninsula

IRP—Integrated Resource Plan

MEA—Matanuska Electric Association—electric utility serving Matanuska-Susitna borough

ML&P—Municipal Power and Light—electric utility serving parts of Anchorage; purchased by CEA in 2019

MOU—Memorandum of Understanding

RCA—Regulatory Commission of Alaska—state body charged with regulating utilities

REAP—Renewable Energy Alaska Project—non-profit promoting renewable energy and energy efficiency in Alaska

RRC—Railbelt Reliability Council

SB 123—Senate Bill 123, 2020 legislation requiring creation of Railbelt ERO